Language Map of the US

Reflections on a Long-Running Side ProjectAt the end of 2022, I was very excited to re-launch a side project of mine: The Language Map of the United States.

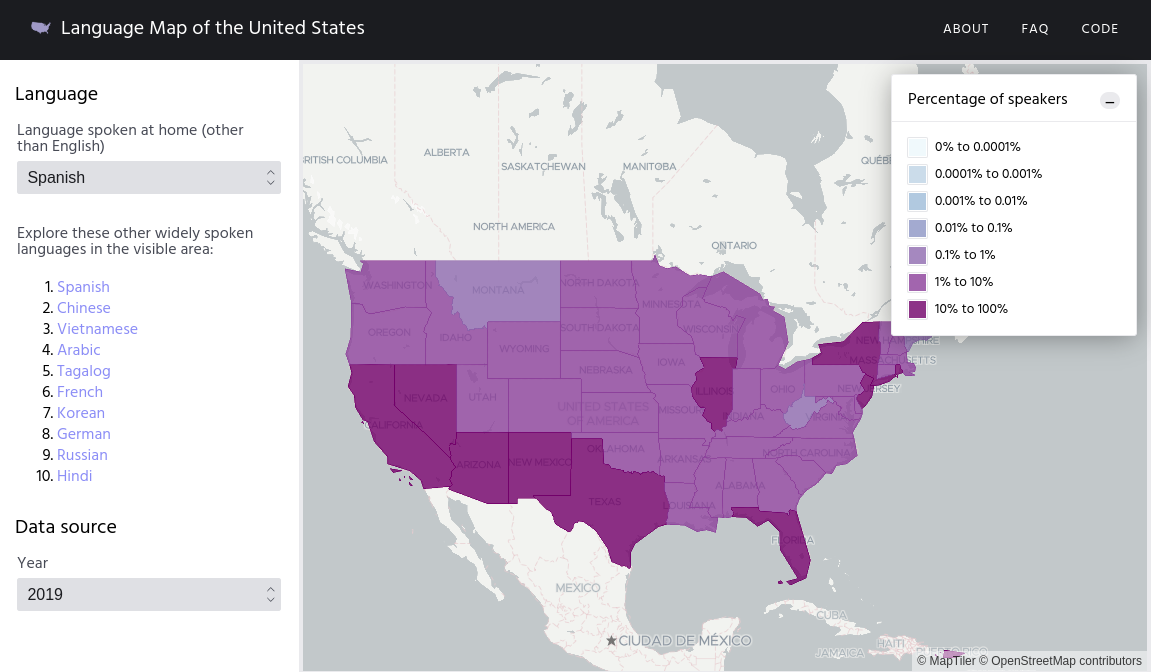

The app uses Census data to allow you to visualize what languages are spoken in the United States, D.C., and Puerto Rico:

|

|---|

| Spanish speakers in the US using 2019 data |

Language Map v1.0

I originally started working on the project five years ago in 2018 before I had any knowledge of, or professional experience with, GIS. I had just gotten a job at Azavea and wanted to make something to learn about the field and relevant technologies.

At the time, I was smitten with Elixir as I was getting more interested in functional programming and wanted to try out the Phoenix web framework. I wrote an API that served GeoJSON which was used to draw geometries (states and subdivisions of states called PUMAs) on a Leaflet map and returned speaker counts based on other filters besides language applied by the user, such as age, citizenship status, and English proficiency. I had been learning Docker at work and containerized the app to flex those muscles and get more reproducible deployments. I deployed it to a VPS – the fastest way I knew at the time to get it into production – and it worked! I had built something cool using open source software and open data. After posting it on reddit, I got some positive feedback and suggestions, made a few changes, patted myself on the back, and shelved the project. I had pushed myself hard to get it out and needed a break.

After the initial launch, I didn’t touch the app. At some point the VPS provider restarted my instance for maintenance and the app didn’t restart gracefully. I tried switching providers to cut down on the hosting cost but I had trouble remembering exactly what I had done to provision the VM appropriately and couldn’t muster up the motivation to figure out how to get it running again. At some point, I got tired of paying the monthly fee for the VPS to host an app in a broken state and shut down the instance. My app was dead and it was a shame, but I’d done what I’d set out to do.

Revisiting the App

Fast forward to the end of 2022. I’d gotten the bug and wanted to bring my app back better than it was before. Drawing on the knowledge I’d gained working professionally in GIS, I wanted to try to re-build and re-deploy the app so it could be hosted nearly for free and with no maintenance in perpetuity, solving the two issues that had done me in the first time around.

It occurred to me that if I reduced some of the filtering functionality – originally one could filter speaker counts by citizenship status, age, etc. – I could deploy the app as entirely static, baking the speaker counts into the metadata of Mapbox Vector Tiles, a newer geographic data format that could be used to efficiently serve the geometries. After that pre-processing had been done to produce the tiles with metadata, the counts could then be aggregated on the frontend instead of being supplied by an API. By only displaying one geolevel at a time, either states or PUMAs, depending on zoom level, I could keep the number of geometries whose speaker counts needed to be aggregated comfortably low so the app would still feel snappy.

A month or two later, the app was relaunched with the same visual look and feel but with better performance. I had added in an oft-requested feature based on previous user feedback to allow for exploring the languages spoken in an area without having to choose a language first. I had also written the data processing pipeline that builds the vector tiles + metadata in a generic way so that multiple years were supported, potentially allowing for the visualization of changes to speaker counts over time.

The best part was that the app cost less than a dollar to host and continuous deployment was set up to make redeploying trivial.

Lessons Learned

This project was a tremendous learning experience with these being the most salient takeaways:

If you can, make it static

A static app is worlds simpler than a dynamic one. There’s no database and no backend. In this case, the app is deployed via Netlify which makes it extremely easy to deploy a static app via a branch-based workflow for free! This approach of course requires data that doesn’t change which worked well for my use case.

That said, the inherent complexity doesn’t disappear by making the app static. There is some fairly involved data munging in my data pre-processing pipeline (read: many bash scripts calling out to GDAL and Tippecanoe), some of which had been handled for me by Postgres/PostGIS previously. But once the vector tiles were baked it was smooth sailing.

Take advantage of the frontend

When I think of frontend development, I often don’t think of CPU-bound tasks. Part of this is due to prevalence of I/O-bound frontend apps out there that handle UI interaction, call out to APIs, and manage state (the vast majority of my professional frontend development experience falls into this category). There’s also JavaScript’s single-threaded nature which can cause CPU intensive tasks to tank your user experience if you’re not careful (web workers can of course be useful here but introduce complexity). However, there are excellent use cases for tasks on the frontend that might typically be done on the backend.

In the case of this app, the size of the data and the nature of the computation – filtering by year and language and summing up speaker counts – are such that no optimizations of any kind have been implemented but it still performs well with no UI jank. Not only is the architecture vastly simplified but no network latency is incurred since there are no network requests being made, aside from those for the tiles themselves which is handled by the frontend mapping library, MapLibre.

(Note that this idea of “Why not just do it on the frontend?” was inspired by DistrictBuilder.)

Talk to your users

This is such an important and basic tenant of software development, but it still bears repeating and I still should have done it sooner. It didn’t occur to me that people would very much want to explore areas without having a specific language in mind (though it seems like a very obvious feature request in hindsight). Ultimately, the filters such as citizenship status and age were not very important since nobody ever mentioned them, and including those extra filters constrained the initial technical implementation, perhaps needlessly.

Know your limits (and make friends with designers)

The app looks great thanks to Alex Lash, a former coworker of mine. I can muddle through with CSS but I am not great at and don’t have design sensibility, so enlisting the help of an expert in this area was a must. She was good enough to volunteer her time to help out this project, and I really appreciate it! Thanks Alex!

Domain knowledge/familiarity with ecosystem & tools is extremely valuable

The v1.0 implementation served up GeoJSON and speaker counts via a REST API and used Leaflet on the frontend. This approach was chosen for expediency since I was more familiar with those tools/architecture (and because I had a vested interest in using the Phoenix web framework for learning purposes). The tools and architecture that I settled on for v2.0 such as jq for working with JSON, GDAL for reprojection, and Tippecanoe to build MVTs (or even vector tiles themselves!) were not even on my radar when I first began to work on the project.

The ACS is an amazing data source

I wanted to explore open datasets as part of this project. The ACS (American Community Survey) is carried out every year by the Census Bureau and collects an incredible amount and variety of information where “Non-English language spoken at home” is only one question among hundreds (see 2019 PUMS Data Dictionary). The documentation and supplemental materials are invaluable as well for those making use of the data.

While I was aware of publicly-available Census data, I didn’t previously know this particular treasure-trove of data existed, how it was structured, or how to work with it, so I would encourage you to keep this incredible free and open resource in mind for your projects.

Inspiration and motivation come in fits and starts

I worked on this project intensely for many months, and then didn’t touch it for years. I did, however, circle back to it eventually. I think it’s important to respect one’s current level of interest, motivation, and of course free time to devote to a side project, given that it is for fun and learning after all.

Documentation and code quality matter

I always try to commit code that I feel at least okay about as per my, perhaps somewhat arbitrary, personal standard of quality. If I’m not happy with it but it’s readable or at least documented, then I have a hope of coming back to it and improving it in the future. If I hadn’t done this for v1.0, I don’t think I would’ve been able to take the project up again! Documenting code even for your future self is important to avoid the project being rewritten or abandoned. I’m happy that I was able to reuse much of the frontend code verbatim for v2.0 of the app because of it being fairly reasonably structured/commented.

Conclusion

I loved working on this project and am super happy with how it has turned out so far. I may very well come back to it again in the future with more feature enhancements (eg. showing changes to speaker counts for a given language over time)!

If you haven’t yet, please take it for a spin:

If you have any feedback/bug reports/suggestions, please create an issue on the GitHub repo.